Guest post by Youssef Soliman, medical student at Assiut University and biostatistician

Conducting a clinical trial risk assessment is now a regulatory expectation and a cornerstone of quality management in clinical research. A risk assessment is a systematic process for identifying and evaluating events that could affect the achievement of a trial’s objectives [1].

In practice, this means examining the protocol, procedures, and trial environment to spot hazards to patient safety, data integrity or compliance. Regulatory guidance (e.g. ICH E6(R2) and FDA guidance) explicitly recommend that sponsors use a risk-based approach to trial design and monitoring [2, 3]. For example, the FDA notes that at the protocol design stage, sponsors should identify critical data and processes (for subject protection and data reliability) and then perform a risk assessment on those elements [3].

This article provides a step-by-step guide and evidence-based strategies to help clinical researchers and sponsors implement effective risk assessment and management practices.

Check your trial design

A thorough risk assessment is essential to protect participants, ensure valid data, and make efficient use of resources. By focusing on the most critical issues up front, risk assessment helps sponsors allocate monitoring and quality-control efforts where they matter most.

Above: the Clinical Trial Risk Tool lets you upload a protocol and will automatically check the protocol design against its checklist, as well as generating a site budget for you.

For instance, FDA guidance emphasizes that sponsors should manage both risks to trial participants (e.g. safety problems) and risks to data integrity (e.g. incomplete or inaccurate data) throughout all stages of the study [2]. In other words, good risk assessment lays the foundation for clinical trial risk management. It ensures that the trial design addresses potential pitfalls (like unsafe procedures or unclear instructions) before they occur.

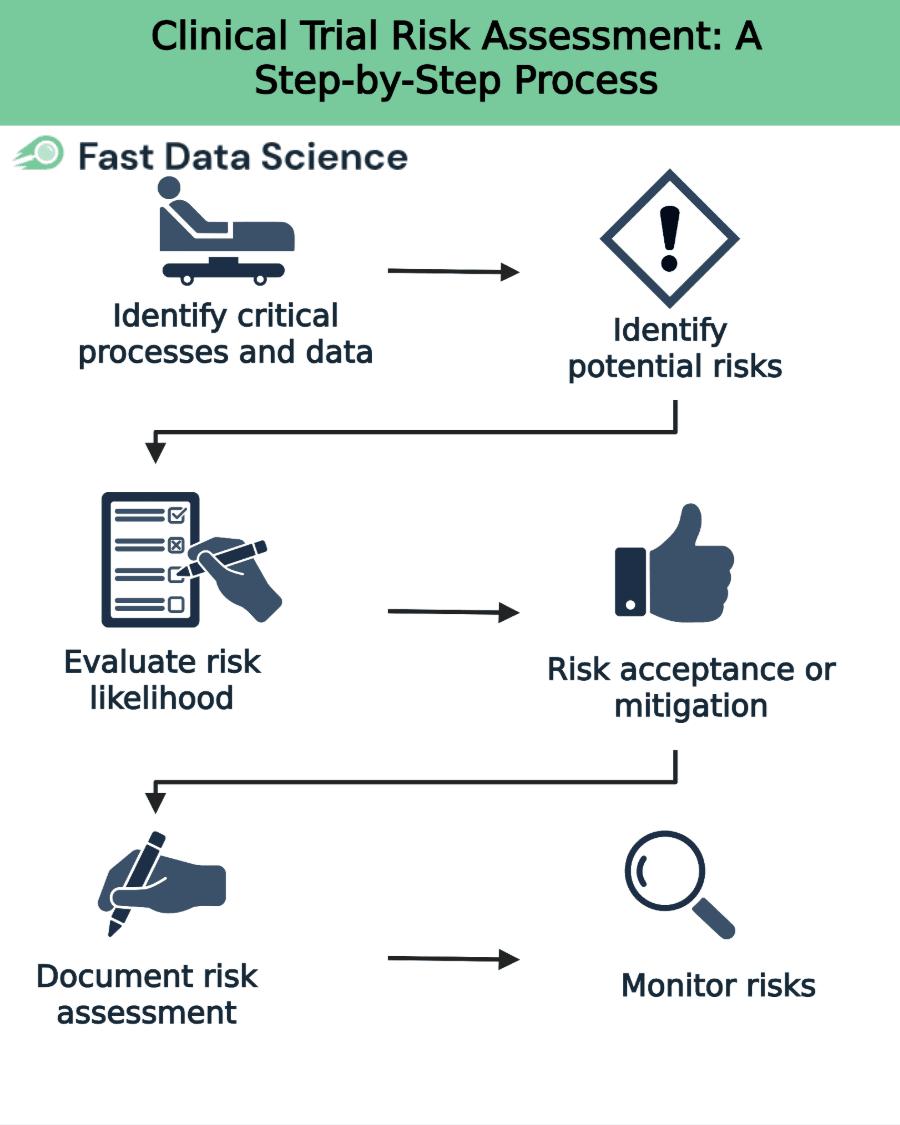

The process of conducting a trial risk assessment can be broken down into clear, logical steps. Each step builds on the last to ensure a comprehensive evaluation and management plan. A recommended approach (reflecting ICH and FDA guidance) is:

First, determine which aspects of the trial are most essential for subject protection and reliable results [2]. For example, critical items may include eligibility criteria, key safety assessments (e.g. informed consent, adverse event reporting), primary endpoints, and essential laboratory tests. Document these critical processes and data points at the trial protocol stage (e.g. in a Risk Management Plan).

For each critical element, list all foreseeable risks or hazards that could threaten it [2]. Consider risks at both the system level (such as SOPs, computerized systems, staff training) and the trial level (such as protocol design flaws, complex procedures or data collection methods) [2]. Examples might include risk of missing data on a primary endpoint, inadequate staff training, delays in drug supply, or protocol deviations (like enrolling ineligible patients).

Assess each identified risk for its probability of occurring and its potential impact on participant safety or data quality. ICH E6(R2) recommends considering factors such as how likely an error is, how easily it would be detected, and its severity if it happens. A common method is to assign a score or rating (e.g. on a 1–5 scale) to each risk’s likelihood and impact, then calculate an overall risk score. High-risk items (high likelihood × high impact) should be highlighted for priority action.

For each risk, decide whether to mitigate, transfer, or accept it. The goal is to reduce unacceptable risks to a tolerable level. Mitigation measures can be built into various aspects of the study. For example, the ICH guideline notes that risk reduction activities may be incorporated in protocol design (e.g. simplifying an endpoint), monitoring plans (e.g. more frequent checks of a safety parameter), agreements (e.g. clarifying roles in contracts), SOPs and training (e.g. additional staff training on a complex procedure). Document the chosen risk controls and residual risks. If a risk is accepted (e.g. minor deviations that won’t affect outcomes), explicitly note why and how it will be monitored.

Record the entire risk assessment process in writing. This typically means filling in a Risk Assessment Log or Risk Register. Include identified risks, scores, controls, and any quality tolerance limits (QTLs) or risk indicators for monitoring. The sponsor should communicate the risk management plan and quality tolerance limits to all relevant parties (sites, monitors, CROs). Clear documentation and communication ensure everyone is aware of critical risks and their role in managing them.

Finally, during trial execution, continuously monitor the defined risk indicators and QTLs. Periodically re-assess risks in light of new data or events. ICH E6(R2) advises sponsors to review risk control measures to ensure they remain effective as the trial progresses. If an indicator reaches a predefined threshold (e.g. excessive missing data at a site), trigger an investigation or corrective action. Update the risk register and actions as needed (for example, add new risks or raise the monitoring intensity on a worrisome site).

This step-by-step process ensures a transparent, repeatable approach to risk assessment. By following these steps methodically, trial teams answer the question “how to conduct a clinical trial risk assessment” in a structured way.

Clinical trial risks tend to fall into several broad categories. Organising risks by category can help ensure all areas are considered. Common risk categories include:

These involve anything that could harm participants or impede safety monitoring. Examples: inadequate informed consent procedures, unanticipated adverse events, or protocol procedures that stress subjects.

These relate to the accuracy and completeness of study data. Examples: missing or incorrect case report forms (CRFs), data entry errors, improper handling of biological samples, or errors in laboratory testing.

These cover deviations from the approved study plan. Examples: enrolling ineligible subjects, protocol amendments not communicated, poor documentation of deviations, or failure to follow inclusion/exclusion criteria.

These refer to issues with the trial’s logistics and execution. Examples: slow site enrolment, key staff turnover, interruptions in drug supply or equipment failure, and inadequate site training or monitoring coverage.

These involve failing to meet legal or ethical requirements. Examples: missing regulatory approvals, late safety reports, breach of confidentiality, or consent forms not updated.

These include the risk of cost overruns or funding shortfalls, which can indirectly impact trial execution. Examples: higher-than-expected patient drop-out leading to extended enrolment and additional costs.

Each trial will have its own specific risks within these categories. When conducting a clinical trial risk assessment, it is important to consider all relevant categories so that no key risk area is overlooked. (For instance, ICH notes that risks should be considered at both the system level and the trial level, which parallels considering both operational and trial-specific risks.)

A practical example of a modern tool is the Clinical Trial Risk Tool. This tool uses natural language processing (NLP) to scan a trial protocol and flag risk factors or “design gaps” automatically. The design and validation of this tool were partly informed by findings from Hayward et al.’s 2019 JAMA study, which evaluated how traditional monitoring practices contributed little to trial informativeness and underscored the need for smarter, risk-based approaches [4].

For instance, it evaluates whether the protocol meets key informativity criteria (such as having clear endpoints, feasible design, etc.) and highlights areas that may need review with the Clinical Trial Risk Tool [5]. In effect, the tool provides a preliminary risk assessment report based on the protocol text, helping trial teams to focus their manual review [5]. The tool does not replace human judgment, but it speeds up the early review and ensures common issues are not missed.

In practice, trial teams may use a combination of manual checklists and software. Many sponsors still rely on spreadsheets or generic risk registers to document risks. However, as the field evolves, more automated solutions are becoming available. When choosing a tool, ensure it can incorporate your trial’s unique risks and update as the study evolves. (Note: whatever tool is used, remember that human oversight of the risk assessment is essential to interpret the findings and plan appropriate mitigations.)

Even with the best intentions, risk assessment can go wrong. Common pitfalls include:

Incomplete or superficial assessment. Skipping steps or failing to identify all critical risks undermines the process. Avoid this by involving cross-functional stakeholders (e.g. clinical, data, safety, and quality experts) in the assessment, and by explicitly considering each category of risk. A tool or checklist can help ensure no major area is overlooked.

Overemphasis on Source Data Verification. Many teams fall back on 100% SDV as their main control, but evidence shows this often brings low value [6, 7]. Relying heavily on SDV can divert resources from more effective controls. To avoid this, focus on truly critical data and issues identified in your risk assessment rather than blanket verification.

Failure to update the risk plan. Trials change over time. New issues may emerge (e.g. a site closure, unexpected adverse events, protocol amendments). A pitfall is to treat the risk assessment as a one-time task and not revisit it. Avoid this by scheduling regular reviews of risk indicators (e.g. monthly risk review meetings). If a risk materialises or grows, revise the mitigation and monitoring plan accordingly.

Poor communication. If the risk assessment and plan are not clearly shared, sites and monitors may not know what to watch for. For example, if sites are unaware of specific QTLs, they won’t help address them. Ensure that all relevant staff understand the identified risks, tolerances, and their roles in mitigation.

Ignoring trial context. Each trial is unique. Applying a generic risk template without considering the specific disease, population or intervention can miss key risks. Customise the risk assessment to the study’s context. Use therapeutic area knowledge and previous trial experience.

Underestimating regulatory expectations. Regulatory authorities now expect documented risk assessment and monitoring. Failing to adequately document the process (or to justify why certain risks were accepted) can lead to compliance issues during inspection. Tie back all decisions to the regulations: for example, ICH E6(R2) explicitly requires a risk-based monitoring approach [1].

By being aware of these pitfalls, trial teams can take steps to avoid them. The key is to execute the risk assessment methodically, keep it current, and ensure transparency. Doing so not only strengthens risk management, but also prepares the team for regulators’ scrutiny.

A well-conducted risk assessment is the cornerstone of effective clinical trial risk management. By systematically identifying, evaluating, and mitigating risks, sponsors can protect participants, safeguard data, and allocate resources efficiently. This guide outlined how to conduct a clinical trial risk assessment step by step, from identifying critical processes to monitoring quality tolerance limits, while also highlighting common risk categories, mitigation strategies, and tools like the for protocol review.

In practice, success depends on clear documentation, cross-functional input, and ongoing diligence. Incorporating scoring systems and software aids can enhance transparency and reproducibility. Staying aligned with regulatory guidance and evolving best practices, such as insights from recent risk-based monitoring studies, is key.

By applying these strategies, trial teams can make risk assessment a practical and impactful element of trial planning. The ultimate aim is a study that runs safely, efficiently, and yields reliable, high-quality results.

Estimating the total cost of a clinical trial before it runs is challenging. Public data on past trial costs can be hard to come by, as many companies guard this information carefully. Trials in high income countries and low and middle income countries have very different costs. Upload your clinical trial protocol and create a cost benchmark with AI Protocol to cost benchmark The Clinical Trial Risk Tool uses AI and Natural Language Processing (NLP) to estimate the cost of a trial using the information contained in the clinical trial protocol.

You can download a white paper about clinical trial cost benchmarking here Estimating the total cost of a clinical trial before it runs is challenging. Public data on past trial costs can be hard to come by, as many companies guard this information carefully. Trials in high income countries and low and middle income countries have very different costs. Clinical trial costs are not normally distributed.[1] I took a dataset of just over 10,000 US-funded trials.

Guest post by Safeer Khan, Lecturer at Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan Introduction The success of clinical studies relies heavily on proper financial planning and budgeting. These processes directly impact key factors such as project timelines, resource allocation, and compliance with regulatory requirements. The accurate forecasting of costs for clinical trials, however, is a highly complex and resource-intensive process. A study by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development found that the average cost of developing a new drug is approximately $2.