Guest post by Youssef Soliman, medical student at Assiut University and biostatistician

Before launching a clinical study, even the most promising idea must be vetted for feasibility. In other words, can this trial be executed successfully in the real world? Feasibility assessments examine practical factors like available patients, site capabilities, timelines, and budget. This step is crucial. A majority of trials encounter delays or enrollment shortfalls (by some estimates, 70–80% of trials) [1], driving up costs and risking failure. Careful feasibility planning helps sponsors avoid impractical or unethical trials that waste resources and needlessly expose patients [2].

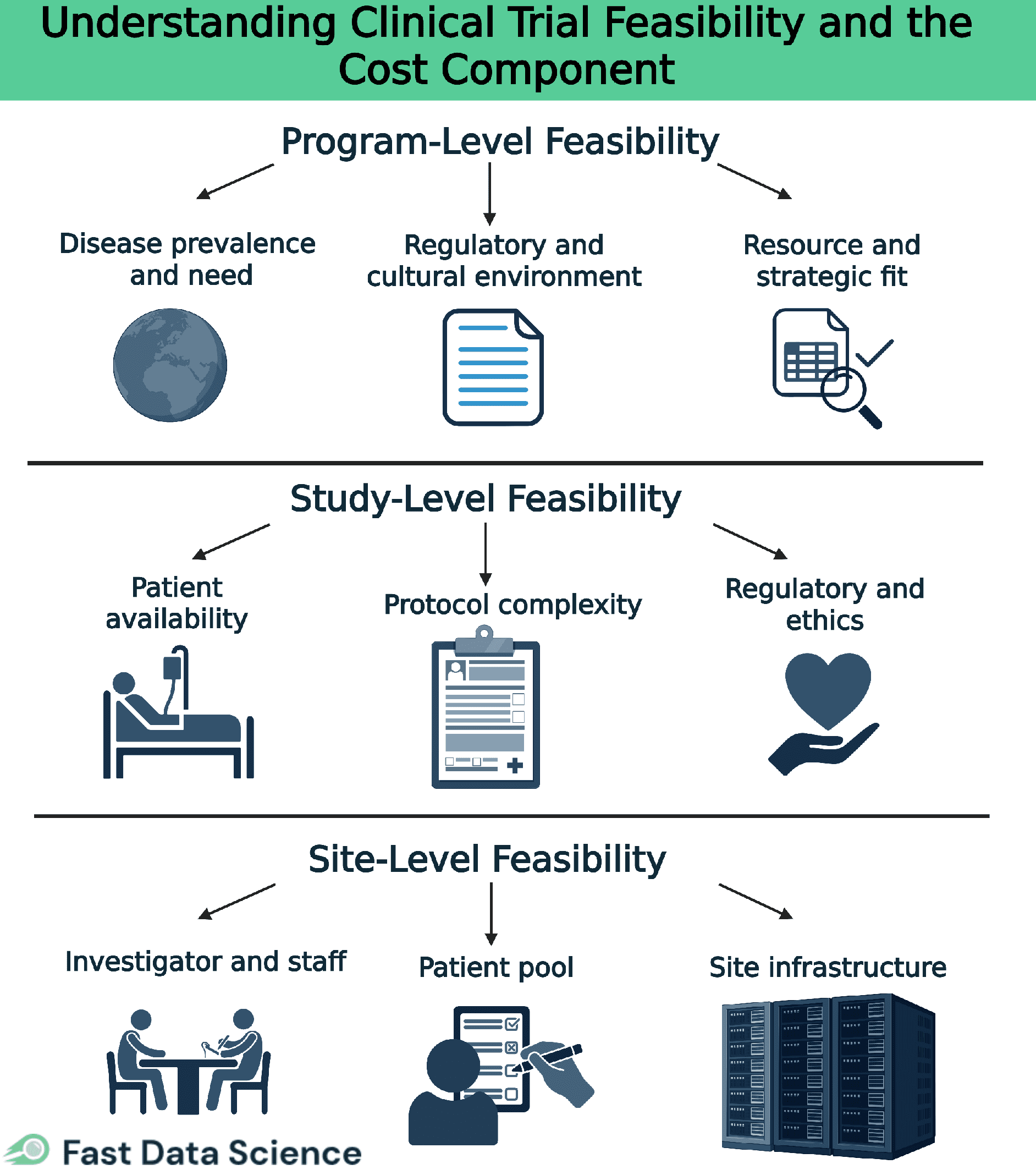

Clinical trial feasibility happens at multiple levels. It starts broad at the program level, then focuses on a specific study, and finally drills down to individual site selection. In this article, we overview each level of feasibility, explain why feasibility is so important for trial design and ethics, and dive into the cost component, highlighting key cost drivers like staffing, site readiness, regulatory needs, patient support, and logistics. We also show how tools such as the Clinical Trial Risk Tool can aid feasibility assessment (e.g. by analyzing protocol risk and complexity), and we share best practices and common pitfalls in feasibility planning [2].

Program-level feasibility looks at the big-picture viability of a clinical development program or therapeutic area before individual trials are designed. At this stage, sponsors assess broad factors such as:

Is the target condition common enough (in the planned regions) to enroll patients across multiple studies? Are there unmet medical needs that justify the program?

What regulatory requirements or ethical norms in target countries could impact all trials in the program? Early conversations with regulators can reveal any major hurdles.

Does the sponsor have the necessary resources (budget, expertise, time) to run the envisioned series of trials? Program-level feasibility ensures the overall plan is realistic and aligned with the company’s capabilities.

By evaluating these factors up front, organizations can decide if a development program is viable or needs re-scoping before proceeding to designing specific studies.

Study-level feasibility asks whether a specific trial (and its protocol) can be executed as planned. Key questions at this level include:

Can the trial enroll the required number of participants in the intended timeframe? This involves checking disease prevalence and ensuring the inclusion/exclusion criteria are not so restrictive that eligible patients will be too scarce. Overly optimistic recruitment targets can doom a trial, so realistic projections are essential [2].

Is the study design practical for sites and patients? Overly complex protocols (e.g. too many visits or invasive procedures) can overburden participants and site staff. Feasibility reviews often recommend simplifying procedures or visit schedules to reduce burden. This step also verifies that sites have the necessary technology and expertise to perform all protocol-required assessments.

Can the trial obtain approvals and meet all regulatory/ethical standards? Feasibility considers local regulatory requirements, IRB review timelines, and any ethical issues in the protocol. A study must be designed in compliance with these factors (e.g. appropriate safety monitoring and informed consent processes) in each region to be feasible.

In short, a trial should only launch if its protocol is both scientifically sound and operationally feasible, as ICH guidelines emphasize. Study-level feasibility often leads to protocol adjustments that align the trial’s ambitions with real-world constraints [3].

Site-level feasibility asks whether each potential trial site can successfully enroll patients and execute the protocol. Key considerations include:

Does the site have a qualified principal investigator and sufficient research staff? Prior experience with similar studies is a big plus. Feasibility checks that the team is trained and can dedicate time to the trial.

Can the site access enough eligible patients? This involves reviewing the site’s patient population and referral networks to ensure a steady pool of participants. Sites may estimate how many patients they can enroll, but those projections are validated against clinical data or past performance to avoid over-promising.

Does the site have the facilities and equipment needed for the study? For example, any required lab tests, imaging, or drug storage must be available (or provided). Feasibility also flags any site-specific setup needs, such as staff training on a particular procedure, and considers how quickly the site can obtain ethics approval and contracts.

By vetting sites on these factors, sponsors select locations that are prepared to meet enrollment goals and follow the protocol reliably. Strong site-level feasibility reduces the risk of mid-trial surprises (like a site failing to recruit or manage data properly).

Feasibility isn’t just an administrative exercise. It directly impacts trial quality, efficiency, and ethics. In trial design, incorporating feasibility (a “quality by design” approach) leads to protocols that are more likely to answer the research question without major issues [3]. In execution, a feasible trial is far less likely to suffer delays or cost overruns, because plans were made with real-world constraints in mind. Ethically, ensuring feasibility is vital: it is not fair to ask participants to join a trial that is unlikely to be completed or yield useful data [2]. Regulators and guidelines echo this; a trial should only proceed when there is confidence it can be successfully and safely executed.

Ensuring a trial is financially feasible is as important as scientific considerations. Many trials falter because they run out of money or encounter unplanned expenses. Key cost drivers to evaluate include:

Staffing: Human resources are often the largest cost. This includes payments to study sites and investigators, as well as sponsor/CRO personnel for monitoring and project management. (Site investigator grants and monitoring activities frequently comprise the biggest portion of a trial budget.) [4]

Site readiness: Getting sites up and running can be expensive. Sites may require new equipment, lab tests, or staff training to execute the protocol. These start-up and infrastructure costs must be budgeted so each site can perform the trial properly.

Regulatory compliance: Meeting regulatory and ethics requirements incurs fees and effort. Think IRB/ethics committee fees, regulatory authority application charges, and patient insurance. Global trials face these in every country, so costs can multiply with each region’s submissions.

Patient support: Recruiting and retaining participants has direct costs. Budget for recruitment outreach, travel reimbursements, accommodation (if patients travel far), and compensation for participants’ time. Providing services like transportation or home nursing can improve retention but should be included in the budget.

Logistics: Trial operations involve significant logistics costs. Manufacturing or acquiring the investigational product, then shipping it (often cold-chain) to sites, is one category. Another is handling biological samples. Shipping specimens to central labs and paying for specialized analyses. These costs grow with the number of patients and sites.

A trial that is scientifically promising but under-budgeted for these elements is not truly feasible. Feasibility assessment should produce a realistic cost projection to ensure the sponsor can cover the trial’s scope [5].

Modern technology can enhance feasibility assessments. For example, the Clinical Trial Risk Tool is an AI-powered system that analyzes a trial protocol to predict potential issues. Using natural language processing, it scans the protocol text and identifies factors that increase trial complexity or risk (such as multiple endpoints, insufficient sample size, or lack of a clear analysis plan) [6]. The tool then provides estimates of the trial’s likelihood of success and even projects the cost based on similar past trials. By highlighting high-risk elements early, tools like this help researchers refine their study design [6]. For instance, suggesting protocol modifications to reduce complexity or better align with feasibility limits.

To improve trial success, sponsors should follow these best practices when evaluating feasibility:

Involve key players (investigators, site staff, patients, regulators) from the start. Their insights can reveal challenges the sponsor alone might miss. For example, patient advocates might point out if the visit schedule is too burdensome, or investigators might foresee recruitment obstacles. Addressing such input early leads to a stronger design.

Use structured methods and real data to guide decisions. Employ feasibility checklists covering all critical areas, and leverage data (e.g. electronic health records or past trials) to estimate realistic enrollment rates. Avoid guesswork; objective data (and even a small pilot study if needed) will make plans more reliable.

Selecting the right sites is crucial. Apply clear criteria for site selection (available patients, staff experience, past performance) and ensure each site understands the protocol before committing. It’s often better to activate a few proven, high-enrolling sites than many sites that might underperform. Good communication and support for sites during planning also set the stage for better execution [1].

Build patient recruitment and retention strategies into the plan. Identify where participants will come from and engage those sources (e.g. community clinics or patient groups) early. Design the study to be as convenient as possible for participants (flexible visit scheduling, travel support) to boost enrollment and reduce dropouts.

By incorporating these best practices, sponsors align the trial’s design with real-world conditions, reducing the likelihood of surprises once the study is underway.

Even with careful planning, certain mistakes can undermine feasibility studies. A common pitfall is relying on overly optimistic projections. Assuming best-case scenarios for enrollment or timelines often leads to overestimating the number of eligible patients or the speed of recruitment. When reality doesn’t match expectations, studies stall or fail. Poor data and analysis can also lead to false conclusions; using superficial data or generic questionnaires without verifying site capabilities or protocol details risks missing critical challenges. Another frequent oversight is neglecting timelines and regulations. Failing to accurately anticipate the duration of ethics approvals, regulatory reviews, or site contracts can cause significant startup delays. Additionally, teams may fall into the trap of confirmation bias, unconsciously shaping the feasibility assessment to support a pre-decided plan. This can mean ignoring red flags or only seeking supportive opinions, which undermines the objectivity of the process. Avoiding these pitfalls is just as important as following best practices—a realistic, evidence-based feasibility assessment, even if it highlights challenges, is far more valuable than pushing ahead based on flawed assumptions that lead to costly delays or failures.

Clinical trial feasibility is the foundation of successful study design and execution. By rigorously assessing feasibility at the program, study, and site levels, researchers ensure their trial is set up to succeed scientifically and operationally. This process also upholds ethics by avoiding trials that would waste participants’ efforts. In planning a trial, considering feasibility from every angle, including the cost component, helps preempt problems and align the protocol with reality. Leveraging modern tools and following best practices further reduces risk. In the end, a well-vetted, feasible trial means higher chances of reaching your goals on time and on budget, to the benefit of both the research team and the patients who put their trust in the study.

Estimating the total cost of a clinical trial before it runs is challenging. Public data on past trial costs can be hard to come by, as many companies guard this information carefully. Trials in high income countries and low and middle income countries have very different costs. Upload your clinical trial protocol and create a cost benchmark with AI Protocol to cost benchmark The Clinical Trial Risk Tool uses AI and Natural Language Processing (NLP) to estimate the cost of a trial using the information contained in the clinical trial protocol.

You can download a white paper about clinical trial cost benchmarking here Estimating the total cost of a clinical trial before it runs is challenging. Public data on past trial costs can be hard to come by, as many companies guard this information carefully. Trials in high income countries and low and middle income countries have very different costs. Clinical trial costs are not normally distributed.[1] I took a dataset of just over 10,000 US-funded trials.

Guest post by Safeer Khan, Lecturer at Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan Introduction The success of clinical studies relies heavily on proper financial planning and budgeting. These processes directly impact key factors such as project timelines, resource allocation, and compliance with regulatory requirements. The accurate forecasting of costs for clinical trials, however, is a highly complex and resource-intensive process. A study by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development found that the average cost of developing a new drug is approximately $2.